Due Diligence on Saturation

Vaporous Modernity

01. Context

The 2008 financial crisis is one of the critical turning points that triggered the current general state of saturation. However, this crisis would not have occurred without crediting Lewis Ranieri, who, in the 1970s, invented a new fiction: the first financial asset tied to mortgage-backed securities. This, combined with the rise of financial capitalism, generated a bubble that burst during the crisis. Numerous interest rate hikes led to widespread mortgage defaults, rendering many of these financial assets worthless.

From a sociocultural perspective, it seems that what caused the crisis was not what determined people's behavior in the following years. Instead, it was the government and central bank bailouts of the funds and banks responsible for the crisis that shaped the reaction.

This acted as a catalyst for a backlash that looked to the past, rejected capital, and embraced authenticity as an emblem. For hipster culture, authenticity meant anything untouched by commerce and untainted by commercialization. However, this situation quickly reversed, turning the movement into the very commercial phenomenon it sought to escape from.

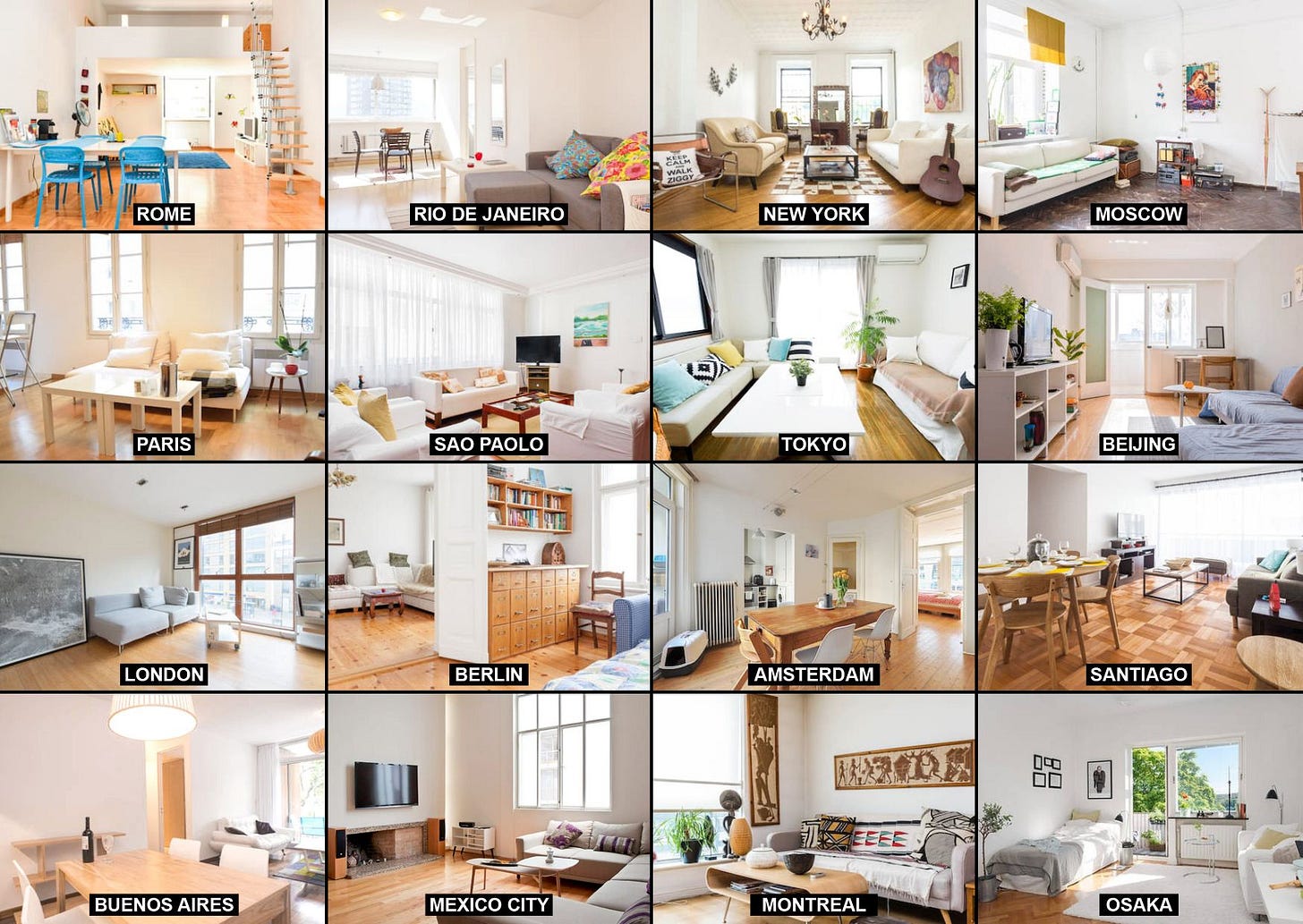

Around 2010, the term "collaborative economy" began to gain traction. The most famous examples include Airbnb and Uber, though many others emerged. These companies essentially offered intermediary platforms to foster trust and connect two individuals. Ironically, this reliance on a company to facilitate understanding between two people underscored their limits. These so-called collaborative economies ultimately revealed themselves as two things: companies whose greatest asset was the data they collected and tools that precariously altered lifestyles.

Panda, OMA and Bengler (2016) via OMA

In 2013, K-HOLE, in collaboration with Box 1824, published the report "Youth Mode: A Report on Freedom", popularizing the term "normcore." This fourth report went viral, turning trend prediction into a trend of its own—a rather "meta" phenomenon. It also marked the start of an abundant classification of micro-trends with the suffix "-core."

Normcore, K-HOLE and Box 1824 (2013) via K-HOLE

In 2017, Venkatesh Rao introduced one of the most pertinent concepts of the time: "premium mediocre". The consumption of seemingly luxurious products at accessible prices created a false sense of aspiration and gratification, masking the insecurities and pressures faced by the millennial middle class in the modern economy.

During this period, digital overload progressively increased, intensifying with the COVID-19 pandemic. This unprecedented event seemed to stop the world entirely. Instead, the physical world partially paused while the digital realm accelerated, offering an escape from the stark reality. Inside our homes, nothing new was happening, leaving us with TikTok and past memories. Nostalgia was heavily capitalized on during this time.

As a result, extreme situations have become normalized. Ongoing wars in various parts of the globe, increasingly evident climate change, heightened political polarization, and other circumstances that would have been significant turning points in other eras now blend into the background.

In 2022, Credit Suisse published the report "Bretton Woods III”, outlining a new global financial order. The uncertainty of this era fueled post-irony, driven by Gen Z, and a proliferation of "-cores" to the point of saturation. Shumon Basar likens this overclassification to screenshots of trends, coining the term "endcore" to describe our arrival at the endpoint of trends themselves.

02. Endcore

Endcore > The era after the end of eras. Marked by a shared sense of a final, historical ending in sight; while simultaneously noting that such an end never actually arrives.

This definition, tied to the latest works by Shumon Basar, vividly illustrates our current situation: the collapse of all narratives. We find ourselves on a path with no clear direction—or with too many simultaneous directions. Adaptability has become the most valuable currency in order to navigate this future reality, as reality shifts repeatedly before we can process it. Young people have long accepted that the dream of living better lives than their parents has faded.

Upcoming technological advances, such as the rise of artificial intelligence, will bring back old acquaintances like nuclear energy to meet the power demands of AI-generated memes or TikTok dropshipping videos. These videos already feature products that, with a screenshot and Google Lens, can be found on Alibaba for a fraction of the cost. Sadly, we will witness more international conflicts and a stronger climate change.

Trends, too, have reached their endpoint ("endcore"). Emily Segal, a former member of the now-defunct K-HOLE collective, addresses this through Nemesis, a consulting firm that she founded. It feels poetic that one of the people who contributed to trend forecasting is now writing its obituary.

“Arguably the prototypical hipster doesn’t really exist anymore. Now we have, for the lack of a better term, creative directors”. This phrase aptly summarizes the evolution of trend dissemination. The original hipster hid their discoveries and never considered commercializing them. Today’s creative directors strive to catch the wave as early as possible, monetize it, and loudly proclaim: "Yes, I was the first one." This has produced such a flood of trends where innovation no longer matters. Instead, observing them and crafting an improved, profitable version has become the goal.

An epitaph to trends appears in the same article: "You can't be early if the thing you're frontrunning is frontrunning you". The sheer volume of micro-trends has saturated its own market, leading to an inevitable collapse.

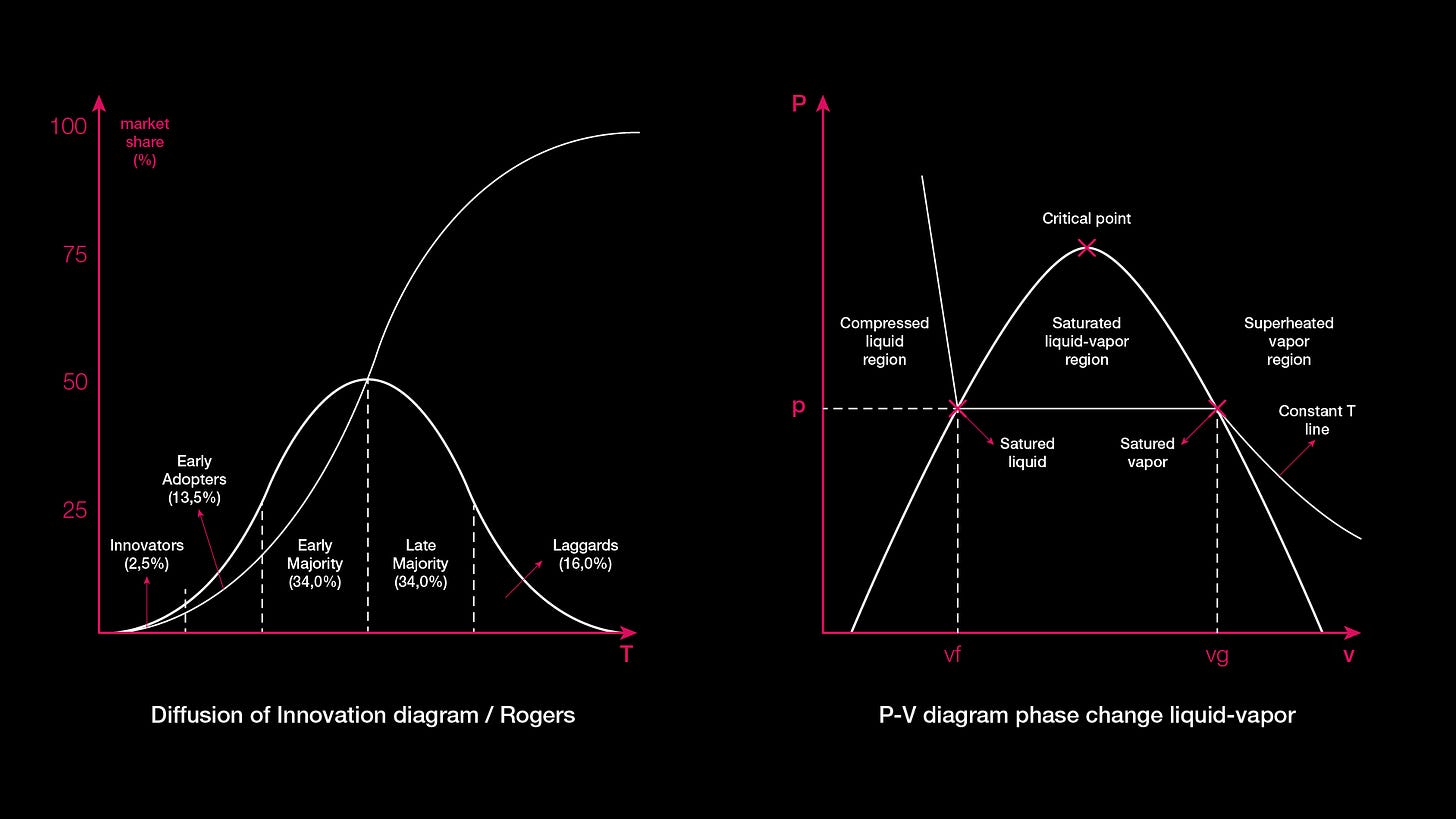

If we examine Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovations theory (1962), we can observe how a trend is developed: from its inception, through a critical point of maximum expansion, to its eventual disappearance. This process mimics the thermodynamic transition in the P-V diagram of a pure substance shifting from liquid to vapor. In its early stages, a trend resembles a liquid state: dense and concentrated, maintained in equilibrium within a small group. As interest grows, "social pressure" pushes the trend to a saturation point—its social boiling point—where it reaches a general audience and massively expands. At this stage, the trend "evaporates", saturating its environment until it dissipates and loses relevance.

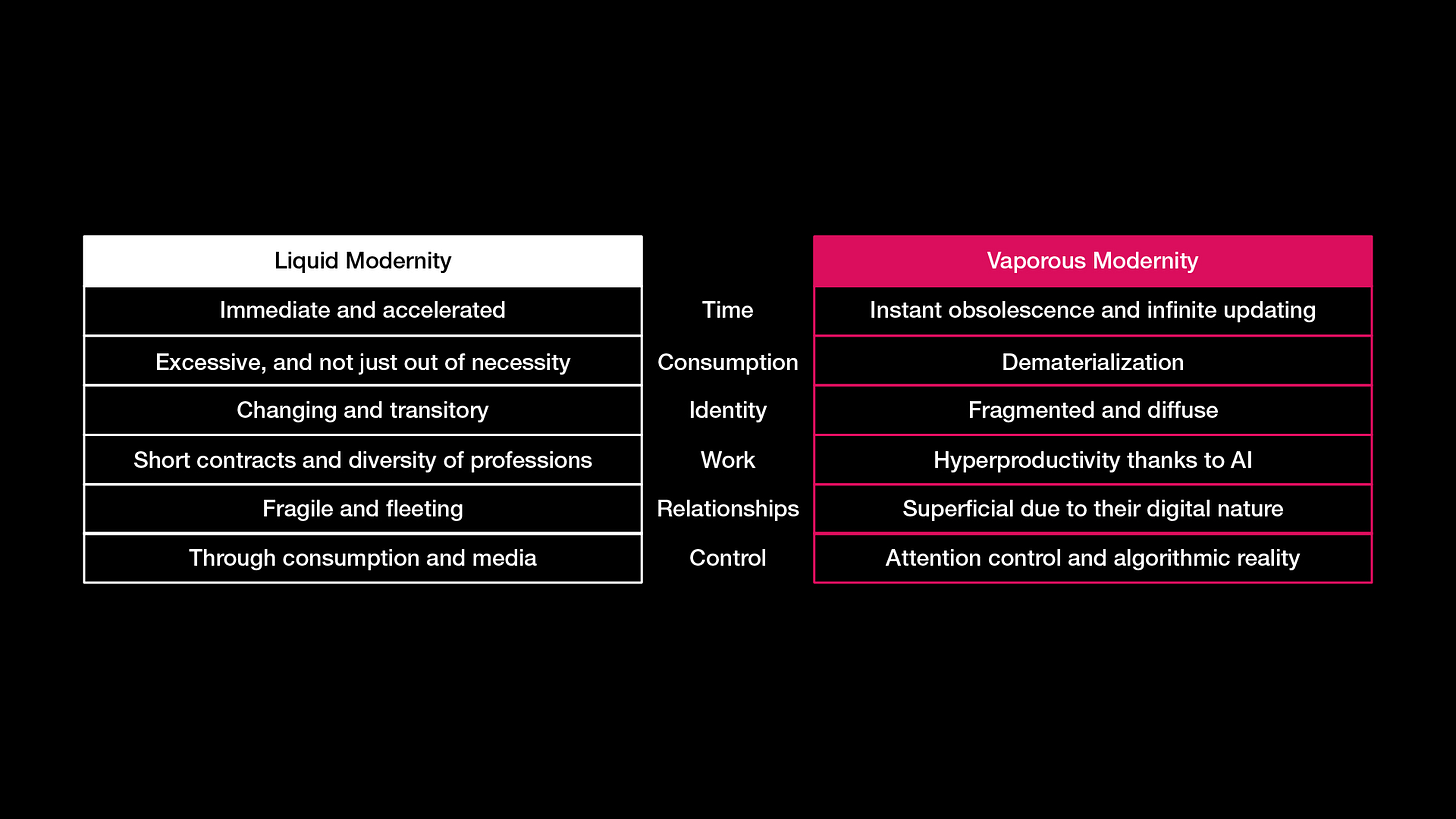

Thus, we have transitioned from liquid modernity to vaporous modernity. Predicting trends once made sense: it was fluid and directional, like a liquid following a clear course. Now, such predictability has simply evaporated.

03. Liquid vs. Vaporous

Zygmunt Bauman, with his theory of liquid modernity, described a significant social shift following the end of World War II. Modernity began to acquire characteristics akin to a liquid: fluid, adaptable, and unstable. Solidity was left behind, giving way to a constantly changing reality.

However, much time and many events have passed since then. The world has undergone numerous transformations, surpassing the boiling point of liquid modernity. We have now entered the stage of vaporous modernity, which is far more intangible, dispersed, and volatile. The main features of this new type of modernity are:

Time. Key concepts: instant obsolescence and infinite updating

Time loses its continuity. Information becomes obsolete in seconds, and the relevance of things lasts only as long as it takes to scroll from one video to the next. FOMO (fear of missing out) and anxiety, sadly, are constant companions as the volume of information overwhelms our capacity to process it. Our brains seem like outdated Intel processors, struggling to keep up with a reality completely saturated with data. In computing terms, we are in a state of constant infinite updates, unable to absorb the present before thousands of new developments flood in.

The present is everything. The past is quickly archived, while the future feels irrelevant as we live in the immediacy of the now. This prevents us from pausing to reflect and analyze the present.

Consumption. Key concepts: dematerialization

Intangible goods and experiences, such as metadata, cryptocurrencies, and other digital assets, are gaining prominence. Social capital is now measured in "likes," and machines are increasingly becoming content creators, relegating humans to the role of consumers.

Dematerialization has even affected the economy. In 1971, the monetary system abandoned the gold standard. Cryptocurrencies have taken this concept further; they lack any physical backing and rely entirely on trust, becoming another type of fiction within the system.

Identity. Key concepts: fragmented and diffuse

Personal identity has become fragmented to the point of being almost diffuse. The two realities we inhabit—physical and virtual—lead each person to possess numerous versions of themselves. From “rinstas” and “finstas” on social media to avatars in virtual worlds, people are compelled to adopt different identities depending on the context.

Authenticity loses all significance. Identity becomes a dynamic and fluid construction, shaped by algorithms and social expectations.

Work. Key concepts: androids

Work is entirely conditioned by the hybridization between people and technology. Hyperproductivity will reach unforeseen levels, as artificial intelligence has not come to free us from work but to make us produce more in less time. We will increasingly depend on these tools that blur the boundaries between the human and the artificial. Deepfakes are a clear example of this fusion.

There is a constant pressure to adapt to new technologies, leading to a symbiotic dependency on them. This will result in inequality and job insecurity for those who do not have the resources necessary to adapt to this new paradigm.

Social Relationships. Key concepts: superficial

Social relationships have an indirect and often superficial nature because they develop through digital platforms. Connections are formed through screens, while algorithms control our emotions and perceptions.

Digital immediacy manages to remove physical barriers, but it also erodes the depth of relationships. As a result, values such as empathy and, above all, human contact are becoming increasingly scarce.

Control. Key concepts: attention control and algorithmic reality

Attention is the most precious commodity, and this is well understood by tech corporations, which seek to monetize it. Everything becomes an opportunity for “engagement,” both in the digital and physical worlds. Algorithms shape our perception of reality, as they are responsible for creating personalized environments for each individual. Thus, the reality we experience is based on the data we generate and what each platform wants us to consume.

04. Future Perspectives and Risk Factors

The future may seem unimportant, but it is coming inevitably. As mentioned earlier, the excessive focus on the present not only deprives us of the ability to reflect on the "now" but also to think about what lies ahead.

We live in a constant state of "everything is possible". This emphasis on the ephemeral makes it harder to find moments for introspection: Will we have a purpose in life, or will we not even have the time to consider it? (If you’re asking yourself this right now, perhaps you’ve momentarily escaped the state of saturation.)

In the near future, we will face circumstances never experienced before—some are actually already happening. Climate change will not only transform the environment but also social and emotional structures. Tragically, just a few weeks ago, many towns in Valencia were affected by a DANA (isolated high-altitude depression). The consequences have been severe: mental, material, and otherwise. People will need each other more than ever to adapt to new situations and move forward.

The social fragmentation of this era carries significant risks and a sense of existential emptiness caused by the lack of deep social connections and the absence of a clear purpose. In this context, countless stimuli and distractions without coherence heighten the sense of collective anxiety.

Still, not everything is so bleak. The present can also serve as a turning point to restructure our priorities and seek personal interests free from algorithms. Amid the haze of vaporous modernity, we may find significant social and technological progress to help us adapt to more complex challenges.

Nothing is set in stone, meaning vaporous modernity could be both a trap and a catalyst for positive change. Everything depends on how well we use our tools to face this new era.

05. Conclusion

It seems we have entered a new paradigm: vaporous modernity. As its name suggests, we still don’t know what it will be like, but we will try to cope with it as best we can.

Industrial cigarettes are a thing of the past; the time of vapers has arrived.

Disclaimer: The ideas and conclusions presented in this article are the result of an analysis and subjective interpretation of the issue at hand. While efforts have been made to provide a reasoned justification for the proposed theory, these conclusions should not be considered definitive or exhaustive. As with problems such as those posed by Gettier, the implications may vary significantly depending on the conceptual framework employed. Readers are encouraged to engage in their own critical reflection, question the premises, and explore alternative perspectives before adopting any definitive stance on the topic discussed. Duplicate Screenshots assumes no responsibility for misinterpretations or consequences arising from the ideas expressed herein.

Love a good Substack relic! And sadly this piece reads very presciently